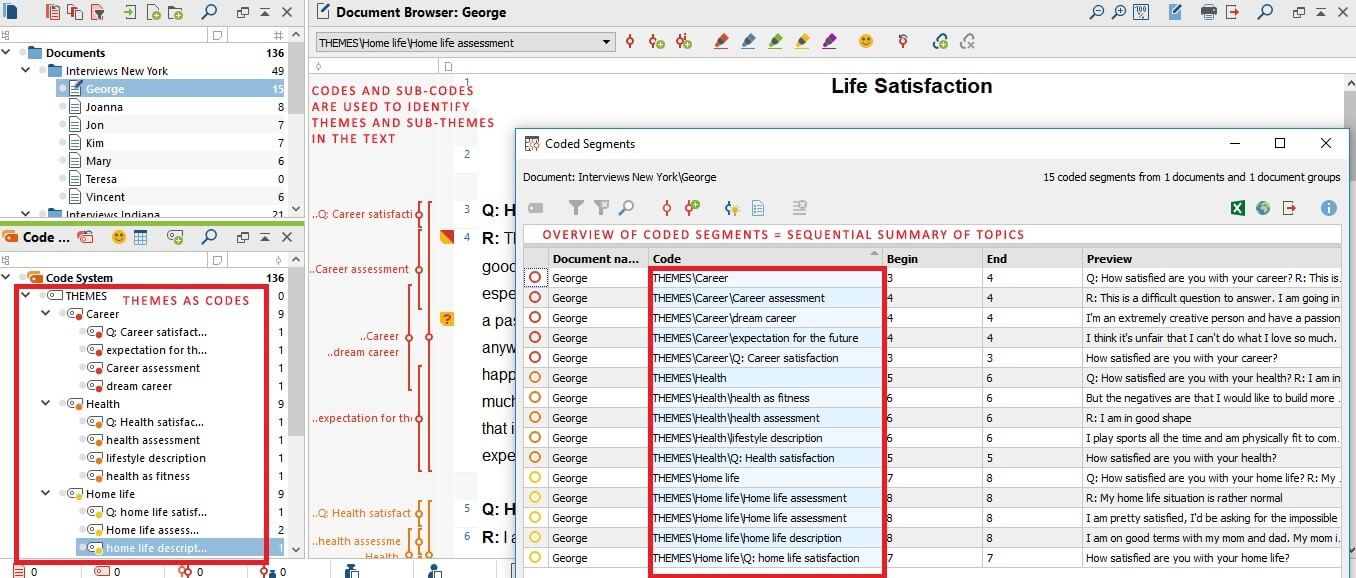

Iterative categorisation was carried out by MB, reviewed by MN and discussed with final agreement. The analysis followed next iterative categorisation according to Neale, 19 which allows for a systematic summary and categorisation of themes directly linked to the original data source. Coding was reviewed by MN and discussed and agreed between MB and MN To ensure intercoder reliability, a sample of six interviews was coded by both researchers and compared for consistency with a resulting high level of concordance. New main codes were assigned for aspects not covered. 18 During the coding process the deductive codes were supplemented with inductive subcodes using phrases or little text segments as unit (see figure 2 as an example of a coding tree).

#MAXQDA ALTERNATIVES SOFTWARE#

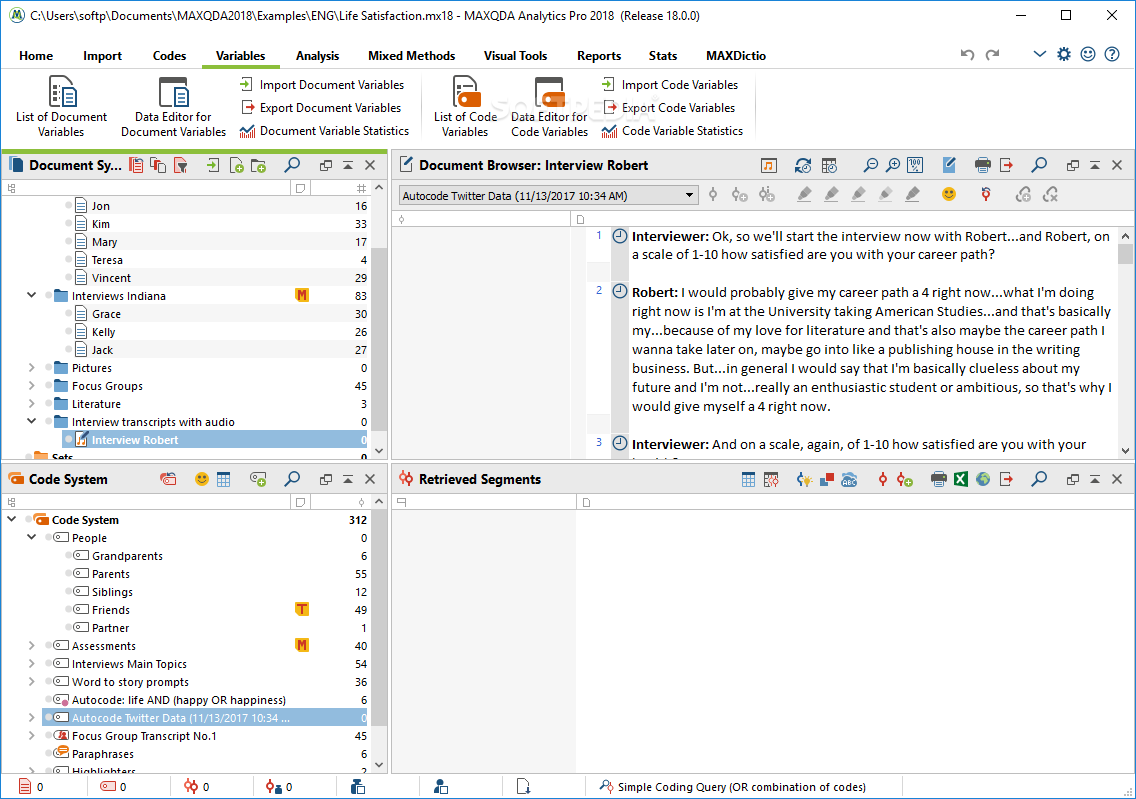

Coding was first done by MB using the qualitative research software MaxQDA. Then, a coding grid was developed with deductive main codes using the G-I-N reporting criteria 8 and ‘implementation (of guideline-based QI)’ as a framework for analysis. Unclear passages could be resolved by verifying the audio-records. Figure 1 gives an overview of the different steps: first, the transcribed interviews were read by MB and MN to get familiar with the content. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim with pseudonymised analysis using qualitative content analysis. All interview participants gave written informed consent. On first contact, possible interview participants were informed about the aims of the study and were sent a topics overview with the possibility to decline. MB did not have prior existing relationships with any participant. Interviewees were contacted by MB via email and followed-up via e-mail and phone, interviews were conducted via phone or skype.

Interview participants were identified either via guideline documents or through contact with research coordinators at the respective guideline organisations. The sample size was planned with 16 on the assumption to interview participants of at least two public and two private organisations acting at the local/regional or at the national level in different countries with the aim to expand the sample according to thematic saturation. 16 17 For each organisation, the aim was to interview both a clinician and a methodologist, who have worked on guideline-based QI, to consider possible different perspectives. Interviewees were selected aiming at purposive maximum variation sampling in relation to guideline development organisations and healthcare settings to reflect a wide range of experiences. The results of this study will be shared within the respective G-I-N working group with the aim to contribute to an international methodological standard.Ī systematic search conducted in preparation of the study up to January 2017 yielded no qualitative publications reflecting on the whole methodological process for developing and implementing guideline-based QI. Further subprojects included an analysis of existing German guideline-based QI, 10 qualitative interviews with German authors from guidelines with and without development of guideline-based QI, 11 a comparison of international and German guideline-based QI published on the same topic 12 and a systematic compilation of existing assessment instruments for QI. 289625106 ), 9 we here report an international qualitative study. In the context of a broader research project aiming to guide the development of an evidence and consensus based methodological standard for the development of guideline-based QI in Germany (DFG Project No. 5–7 To enable an international comparison and harmonisation of approaches, the Performance Measures Working Group of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N) published reporting standards for guideline-based performance measures in 2016. 4 However, the link between guideline recommendations and QI is often neglected and international methodological standards for the development of guideline-based QI are still lacking. 1–3 An QI can be defined as a ‘measurable element of practice performance for which there is evidence or consensus that it can be used to assess the quality, and hence change in the quality, of care provided’. Evidence-based clinical guidelines play an important role in healthcare and can be a valuable source for quality improvement ideally monitored by guideline-based quality indicators (QIs).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)